Пруритогены или вещества вызывающие зуд

|

|

|

|

|

Пруритогены, или пруригены (от лат. prurigo — зуд) — вещества вызывающие зуд, в литературе посвященной нелетальному химическому оружию, упоминаются незаслуженно редко и это несмотря на то, что в годы Второй мировой войны английская разведка их широко использовала для диверсий на оккупированной немецкими войсками территории.

Интерес к боевым отравляющим веществам с изнуряющим, причиняющим боль или страдания, но не смертельным действием резко возрос после успешного применения на фронтах Первой мировой войны «горчичного газа». С этой точки зрения, пруритогены могли оказаться даже предпочтительнее иприта, так как действовали «более гуманно», не оставляя не теле ужасных волдырей и язв, и в то же время, противогаз, хорошо защищавший от всех известных в те годы раздражающих ОВ, был против них бессилен.

В 1917–1919 годах Военное министерство Великобритании проводило полевые испытания новых видов химического оружия, среди которых было и такое необычное, как стеклянная пыль. О действии это нового оружия на человека подробностей не публиковалось, но известно, что стеклянные волокна или пыль при попадании на кожу вызывают сильный зуд. В конце концов англичане убедились, что применение частиц стекла в форме пылевого облака неэффективно в боевых условиях[33].

В монографии известного польского токсиколога В. Линдемана, изданной после Первой мировой войны, в качестве одного из самых сильнейших ОВ вызывающих зуд приводится сульфоциановый этилен C2H4(NCS)2 и не исключается его использования в качестве химического оружия[35].

В 20–30-х годах в лаборатории известного фармаколога Эрнеста Форно, по совместительству занимавшегося разработкой химического оружия для французского правительства, изучали раздражающее действие изооктил пирогаллола. Это вещество, имеющее структурное сходство с природным ирритантом лакколом, вызывало у человека зуд, а в более высоких дозах оказывало кожно-нарывное действие. Всего в лаборатории Форно было получено и направлено для дальнейших испытаний в артиллерийских снарядах около 100 кг этого отравляющего вещества[28].

Впившиеся в палец трихомы Мукуны зудящей

(фото: Armstrong W.P., 2010)

Во Вторую мировую войну британская разведка широко применяла пруритогены для диверсий на оккупированных территориях с целью подорвать моральный дух солдат Вермахта. Первыми успешно опробовали «зудящий порошок» греческие подпольщики, они обильно посыпали секретным английским средством простыни немцев, расквартированных в домах и бараках. Немецкие солдаты, страдавшие от постоянного невыносимого зуда, ничего не заподозрили и считали, что стали жертвами вшей. Позже, зудящий порошок под видом «средства для ног» начал поставляться в Данию и Норвегию, где состоявшие в Сопротивлении работники прачечных, стали посыпать им нижнее белье, брюки и воротники рубашек немецких офицеров. Иногда его даже засыпали в презервативы в борделях, которые посещали немецкие военнослужащие[26].

Наибольшего успеха добились норвежские подпольщики, когда смогли получить доступ к униформе германских подводников. В ежеквартальном отчете, подготовленном британским Управлением специальных операций (УСО) для У. Черчилля, секретная служба сообщала, что с помощью зудящего порошка удалось причинить страдания «в самых нежных частях человеческой анатомии» 25 000 немецким морякам[30].

О составе английского зудящего порошка существуют две версии. По одной из них он изготавливался из мельчайших частиц стекловолокна[27], согласно другому источнику в качестве зудящего порошка применялись «крошечные волоски семян», вероятно, имеются в виду стручки бархатной фасоли[27].

Последнее упоминание о возможности использования зудящего порошка в качестве инкапаситанта встречается в одном довольно старом документе Министерства обороны США под названием «Подавление массовых беспорядков: Анализ и Каталог» (1969). Среди потенциальных пруритогенов упоминаются бархатная фасоль (Mucuna pruriens), протеолитические ферменты и растворы кислот. В статье также говорится, что основные усилия должны быть направлены на поиски подходящего синтетического вещества[11].

Интерес к химическим пруритогенам постепенно угасал и за последующие полстолетия не появилось какой-либо новой информации о разработке химического препарата способного вызывать у человека непереносимый зуд и пригодного для использования в качестве инкапаситанта.

Зудящие порошки

В состав коммерческих «зудящих порошков» (Itching Powder) входят, как правило, ингредиенты вызывающие зуд путем механического раздражения кожи. Такой порошок представляет собой мельчайшие частички в форме острых игл или кристаллов с заостренными краями, благодаря которым они способны проникать в поверхностные слои кожи. Хотя производители и не торопятся раскрывать свои ноу-хау, все же чаще всего «зудящие порошки» это просто размолотые в пыль семена клена (Acer) или волоски бархатной фасоли (Mucuna pruriens). В Германии «зудящий порошок» изготавливают из кутикул роз (на самом верхнем рисунке второй справа)[32].

|

|

|

|

| Семена клена | Плод Бархатной фасоли | Плод шиповника | Глохидии опунции |

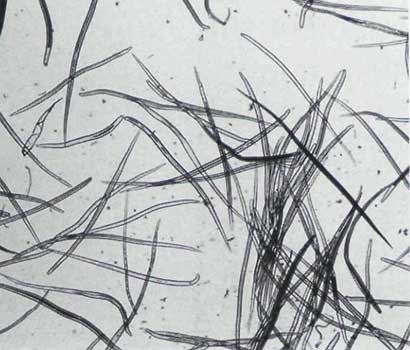

Бархатная фасоль (Mucuna pruriens). Другое название этого вьющегося растения из семейства бобовых говорит само за себя — Мукуна зудящая. Трихомы (от греч. tríchōma — волосы) — оранжевые волоски покрывающие плод этого тропического растения наиболее распространенный компонент «зудящих порошков». Трихомы мукуны настолько малы, что 450 трихом весят всего 1 милиграмм[10].

В 1995 году Шелли и Артур (Shelley W.B., Arthur R.P) по контракту с армией США провели подробное экспериментальное исследование бархатной фасоли. Им удалось установить, что для возникновения зуда у 90% людей достаточно всего одной трихомы, при этом интенсивный зуд возникал через 15–30 секунд и длился в среднем 3–5 минут[20]. Действующим веществом трихом является протеолитический фермент мукунаин, который по механизму действия относится к агонистам рецепторов, активируемых протеазами PAR2 и PAR4[21].

В Венесуэле, во время религиозных праздников, местные шутники из бумажных трубок выдувают порошок Mucuna pruriens в сторону прохожих, обрекая тех на долгие часы изнуряющих почесываний.Трихомы нашли и более благородное применение в этнической медицине — смешанные с медом они оказывают глистогонное действие.

Клен (Acer). Если потереть друг об друга похожие на латинскую букву «V» семена-крылатки клена, то с них начнут осыпаться мельчайшие волоски. Потратив на это занятие немного времени, вы сможете из нескольких десятков семян в домашних условиях получить целую чайную ложку самодельного «зудящего порошка»[6,7]. Такой порошок продается в некоторых американских магазинах торгующих различными «товарами для розыгрышей». Также сильный зуд вызывают опушенные семена платана.

Шиповник (Rosa canina) — тончайшие волоски расположенные на внутренней поверхности плодов шиповника (особенно диких сортов) при попадании на кожу вызывают сильный зуд. Чтобы добыть кутикулы, вначале содержимое плода собирают в отдельную емкость, помещают на 10–15 минут вблизи кипящей воды, чтобы они впитали влагу, а затем высушивают[7]. Есть похожий способ получения «зудящего порошка» из кутикул обычных роз, также известный как метод «Ромео и Джульеты». Волоски кутикул, расположенные внутри бутона, обрабатываются таким же способом, как и содержимое плодов шиповника[31].

Опунция (Opuntia). Очень интенсивный и продолжительный зуд вызывают глохидии кактусов из рода опунций. Глохидии — это тончайшие, острые и жесткие колючки в виде крючков, которые при контакте с кожей или одеждой легко обламываются и впиваясь в кожу вызывают мучительный зуд. Часто избавиться от таких «микрозаноз» можно только вместе с поверхностным слоем эпидермиса, тщательно обработавши пострадавшие участки кожи пемзой.

Крапива Тунберга

Безжалостное оружие ниндзя

Крапива Тунберга. О том, что сильный кожный зуд может довести человека до бешенства, и даже безумия было известно еще полумифическим японским ниндзя. Из крапивы Тунберга (Urtica thunbergiana) они изготавливали мельчайший порошок которым посыпали нижнее белье или просто высыпали за шиворот противнику. В 2006 году тайские ученые смогли объяснить механизм раздражающего действия этой крапивы — как выяснилось, болевую реакцию вызывают щавелевая и винная кислоты, а не гистамин и серотонин, как предполагалось раннее[5]. Вероятно, мельчайшие кристаллики этих кислот при попадании на кожу и вызывают зуд.

Диффенбахия. Способность диффенбахий вызывать сильный зуд при контакте с кожей обусловлена наличием в их соке микрокристаллов солей кальция. Млечный сок Dieffenbachia seguine известной на Гаити как «думбакан», входит в состав яда зомби и известен не только своей способностью вызывать нестерпимый зуд.

Диффенбахия

Орудие пыток плантаторов Гаити

В XIX веке плантаторы в качестве наказания заставляли своих рабов жевать листья диффенбахии. Содержащиеся в этом растении мельчайшие, острые как бритва, кристаллы оксалата кальция вызывали сильнейший отек слизистой оболочки гортани и временную немоту. При попадании в глаза сок этого ядовитого растения вызывает временную слепоту.

Бамбук. Стебли некоторых видов бамбука покрыты пушистыми волосками, которые при контакте с кожей могут вызывать дерматиты, сопровождающиеся сильным зудом[9]. В наставлениях Армии США (B-720 TIPS) даже приводится рекомендация не развешивать одежду на зеленых побегах бамбука, так как его пух действует подобно «зудящему порошку»[12].

Минеральная вата — сильный, но очень опасный пруритоген. Дераматит вызванный минеральной ватой очень тяжело поддается лечению, а попадание в глаза может закончится слепотой.

Для возникновения зуда не обязателен контакт химического вещества с кожей, зуд может возникать и при других путях введения препарата. Талассин — спиртовая вытяжка из щупалец актиний, вызывает у животных сильный зуд при внутривенном введении в дозе 0,1 мг/кг. После инъекции талассина собаке, через 1–2 минуты животное приходило в большое возбуждение, сильно пошатывалось и чихало, чесало лапами уши и терлось носом об пол, через 10 минут зуд распространялся на все тело, коньюктива и кожа живота краснели[29]. В начале прошлого века фармакологи пытались использовать талассин для тестирования противозудных лекарственных препаратов, но из-за высокой токсичности и непостоянного состава препарата, вынуждены были отказаться в пользу более безопасных методик.

Более перспективным и безопасным пруритогеном считается Интерлейкин 31 (Interleukin 31), который участвует в патогенезе таких хронических воспалительных заболеваний, как атопический дерматит и экзема. Это вещество вызывает интенсивный и продолжительный зуд у мышей, собак и обезьян при внутривенном введении в дозе всего 1 мкг/кг[34]. Возможно, он будет также активен и при ингаляционном воздействии.

Некоторые лекарственные вещества способны вызвать зуд при приеме внутрь. Хлорохин — считается препаратом выбора для профилактики малярии, однако почти у 70% процентов людей он вызывает нестерпимый зуд, из-за которого многим приходится прерывать прием.

Кроме химических и механических раздражителей чувство зуда у человека может вызывать стимуляция переменным электрическим током с частотой 50 Hz и длительностью импульса 2 мс и выше[23].

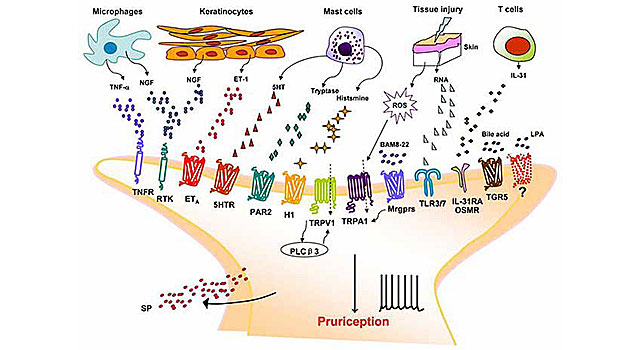

Механизмы зуда и экспериментальные пруритогены

Если раньше считалось, что боль и зуд имеют одинаковые рецепторные механизмы и передаются по одним и тем же С-волокнам, то полученные в последние годы данные все больше указывают на существование специфических рецепторов зуда. По мнению Синьчжун Дуна (Xinzhong Dong) и его коллег из института Джонса Хопкинса на эту роль претендуют рецепторы MrgprA3+ реагирующие исключительно на вещества вызывающие зуд. Нейроны MrgprA3+ расположены в ганглиях задних корешков и ответственны только за иннервацию эпидермиса, так как чувство зуда может возникать только в коже, в отличие от боли, которую мы можем ощущать в мышцах, суставах и различных органах тела[18].

В эксперименте зуд вызывают субстанция P, серотонин, фактор активации тромбоцитов, арахидоновая кислота[1]. Еще одним вероятным кандидатом на роль эндогенного медиатора зуда сегодня считается лейкотриен B4. Введение внутрикожно 0,000 000 01 грамма лейкотриена B4 через 3 минуты вызывало у грызунов получасовой приступ жесточайшего зуда[2].

Лейкотриен В4

У человека лейкотриен B4 вызывает кожную воспалительную реакцию начиная с дозы 5 нанограмм и достигающую максимума при 500 нанограммах. Воспаление возникает через 12–24 часов поле воздействия и сохраняется в течение нескольких дней, оставляя после себя коричневатую пигментацию. Предполагают, что лейкотриен B4 играет важную роль в патогенезе псориаза, так как псориатические бляшки содержат его в больших количествах[3]. Очень похоже, но вероятно через другие механизмы, действует ноцицептин (1-100 нмоля), пептидный лиганд опиоидных рецепторов ORL-1[4].

| Вещество | Фармакологическая группа |

Эффективная доза |

Способ введения |

Ref |

| гистамин | агонист H-гистаминовых рецепторторы |

10 мкг | мыши, внутрикожно |

[14] |

| субстанция P | агонист нейрокинновых рецепторов NK1R |

100 нмоль | мыши, внутрикожно |

[13] |

| лейкотриен B4 | агонист лейкотриеновых рецепторов LTB4 |

0,01 мкг (0,03 нмоль) |

мыши, внутрикожно |

[13] |

| TFLLR-NH2 | агонист рецепторов, активируемых протеазами PAR1 |

100 нмоль | мыши, внутрикожно |

[17] |

| SLIGRL-NH2 | агонист рецепторов, активируемых протеазами PAR2 |

10–50 мкг | мыши, внутрикожно |

[14] |

| AYPGKF-NH2 | агонист рецепторов, активируемых протеазами PAR4 |

100 нмоль | мыши, внутрикожно |

[17] |

| ноцицептин | лиганд опиоидных рецепторов ORL-1 |

30 нмоль | мыши, внутрикожно |

[15] |

| 12(S)-HPETE | метаболит арахидоновй кислоты | 0,017 мкг (0,05 нмоль); |

мыши, внутрикожно |

[16] |

| BAM8-22 | агонист MrgprC11 | 0,000012 мкг | человек, внутрикожно |

[19] |

| Вещество 48/80 | либератор гистамина | 0,3–10 мкг | человек, внутрикожно |

[25] |

Большинство известных синтетических и природных пруритогенов проявляют активность в узком диапазоне доз и только при субэпидермальном введении, что делает невозможным их применение в качестве инапаситантов. Использование в качестве носителя веществ тип ДМСО, не всегда возможно из-за пептидной природы большинства наиболее активных пруритогенов.

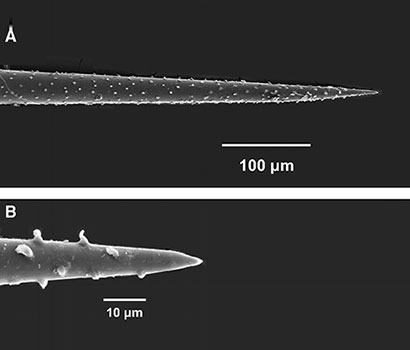

В экспериментальной медицине для внутрикожных инъекций пруритогенов используют обработанные трихомы бархатной фасоли (Mucuna pruriens). Для этого их вначале нагревают до определенной температуры в автоклаве, затем пропитывают раствором пруритогена и высушивают. Эта методика была предложена и успешно опробирована П. Сикандом с коллегами (Sikand P, et al.) на капсаицине, гистамине и BAM8-22. При длине трихомы 2 см, диаметре 1–3 μm и использовании для пропитывания растворов с 10%-концентраций активного вещества, каждый такой «микрошприц» способен доставить в организм около 0,000 003 миллиграмма активного вещества. Однако даже такого количества гистамина оказалось достаточно, чтобы вызвать приступ зуда, даже более интенсивного, чем от необработанной трихомы[19,22]. Для сравнения, вещество BAM8-22 вызывает зуд при введении всего 120 пикограмм, или 0,000 000 12 миллиграмма[19].

|

|

|

Трихомы бархатной фасоли (слева) и щетинки кутикулы шиповника (в центре) и стекловолокно (справа) при большом увеличении

При таком способе введения достигается высокая эффективность, при минимальном риске побочных эффектов, так как в организм попадают субмикрограммовые количества активного вещества. Очевидно, что подобным образом можно внутрикожно вводить и другие вещества с высокой биологической активностью типа альгогенов, токсинов (XR, PG) и биорегуляторов, не способных самостоятельно проникать через неповрежденную кожу.

Лечение поражений

Для лечения зуда вызванного механическими раздражителями («зудящие порошки», трихомы, глохидии, стекловолокно или стекловата) рекомендуется:

- избавиться от загрязненной одежды;

- ни в коем случае не прикасаться и не расчесывать пораженные участки тела;

- если возможно, попытаться с помощью увеличительного стекла и пинцета удалить видимые иглы или волоски;

- орошение кожи сильной струей прохладного(!) душа без мочалки и мыла, не растирать кожу полотенцем;

- механическое удаление раздражителя с помощью клейкой ленты (лейкопластырь, скотч, в крайнем случае — изолента), эпиляционного воска и даже пластилина.

В случае непрекращающегося зуда может потребоваться лечение охлаждающими, противогистаминными и анестезирующими мазями и кремами, а при тяжелом течении — местная кортикостероидная терапия.

Неизвестно, был ли найден химический пруритоген, пригодный для применения в качестве инкапаситанта, поэтому лечение не рассматривается.