Urticants I. Phosgene Oxime

U.S. military analysts' interpretation of a chemical weapons deployment utilizing Soviet Mi-24 "Hind" helicopters

The category of urticant chemical warfare agents (urticants) encompasses several halogenated oximes, with phosgene oxime (CX) being the most extensively studied compound. Phosgene oxime exhibits a unique combination of properties characteristic of three distinct categories of chemical agents: irritants, pulmonary agents, and vesicants. The term "urticant" derives from the Latin "urtica" (nettle), referring to these compounds' capacity to induce dermatological lesions similar to nettle stings. At elevated concentrations, these agents initially produce pruritic white vesicles, which subsequently develop into deep ulcerations characterized by prolonged healing periods.

Phosgene oxime (CX)

Agent CX (US), Nesselstoff, Kanton, Mt (Germ), Hornet Gas, Nettle Gas

Chemical and Physical Properties. Phosgene oxime exists as colorless prismatic crystals with a melting point of 39°C and exhibits a characteristic pungent odor that, resembles new-mown hay at low concentrations[35]. Pure phosgene oxime undergoes partial decomposition during boiling at 129ºC. The compound demonstrates high solubility in water (70%) and most organic solvents.

Stability in Storage. In aqueous solutions, it forms stable hydrates that undergo extremely slow degradation[36]. At room temperature and neutral pH, only 5% of phosgene oxime decomposes over a six-day period. The crystalline form exhibits lower stability to photochemical degradation and humidity, undergoing complete decomposition within 3-4 weeks to yield hydroxylamine, carbon dioxide, and hydrochloric acid. The resultant hydroxylamine subsequently oxidizes to water and nitrogen. In the presence of trace amounts of ferric chloride, the compound undergoes explosive decomposition[35].

Stabilization. Various stabilizing agents have been employed, including nitromethane, ether, dioxane, dimethoxybenzene, chloropicrin, and glycine[22,54]. According to German chemists, phosgene oxime gelatinized with polystyrene retained its activity for many months, which made it potentially suitable for use in aircraft spraying[94]. Solutions of phosgene oxime in ethyl acetate demonstrate extended stability with preserved activity[1].

The phosgene oxime exhibits high miscibility with numerous chemical warfare agents; during the 1930s and 1940s, researchers investigated its potential to enhance the toxicity and rapid action of lewisite and sulfur mustard[92] (mixtures designated as CXH and CXL) as well as nitrogen mustard.

Volatility. The compound exhibits significant volatility characteristics: at 20°C, its maximum vapor concentration reaches 1,800 mg/m3, increasing substantially to 76,000 mg/m3 at 40°C, facilitating rapid achievement of lethal concentrations[55].

Persistence. The on-the-ground persistence of phosgene oxime is approximately 2 hours[54], which is why it was considered unsuitable in the Soviet Union for contamination of the terrain[94].

Penetrative abilities of the phosgene oxime through protective clothing were reported to be 3–3.5 times higher than those of iperyt. Gas capes provide protection against phosgene oxime vapors for only 5–10 minutes[94] The vapor phase exhibits significant reactivity with rubber materials. While early hypotheses suggested potential degradation of protective respiratory equipment, subsequent experimental investigations failed to substantiate these concerns.

Application. During World War II, the most likely scenario for the use of phosgene oxime was considered to be its dispersion from spray tanks by aircraft flying at altitudes of up to 100 meters[92].

Monochloroformoxime (CY, formyl chloride oxime), the first compound synthesized in the halogenated oximes series, was prepared by J. Nef in 1897 via the reaction of sodium cyanate with hydrochloric acid at 0ºC.

NaO–N=C + 2HCl → ClHC=N–OH + NaCl

The initial synthesis of phosgene oxime was accomplished in 1929 by German chemists W. Prandtl & K. Sennewald through the reduction of trichloronitrosomethane using hydrogen sulfide[19].

During World War II, researchers in the United States and United Kingdom investigated three distinct synthetic approaches[24]:

1. Reduction of trichloronitrosomethane utilizing either hydrogen sulfide or aluminum amalgam. This methodology yielded a low-quality product characterized by rapid degradation within 24 hours.

2. Chlorination of fulminic acid or mercury fulminate. This synthetic route, primarily investigated in British laboratories, achieved yields of 24-45%.

(C=N-O)2Hg + Cl2 → (Cl2C=N-O)2Hg + H2O → Cl2C=N-OH

Double recrystallization of the product yielded a sufficiently pure compound exhibiting stability for several weeks without significant degradation. Additional research demonstrated that treatment of mercury fulminate with cyanogen chloride produced chlorocyanooxime[37].

3. Chlorination of isonitrosoacetone, which produced crude phosgene oxime in 55-60% yield[25].

Cl2 + H2O → HOCl + HCl

CH3COC(Cl)=N-OH + HOCl → CH3COOH + Cl2C=N-OH

This synthetic methodology underwent development in the United States during World War II. The phosgene oxime produced via this route was subsequently transferred to the University of Chicago's toxicological laboratory for comprehensive evaluation.

In 1948, prominent military chemist E. Gryszkiewicz-Trochimowski, who had emigrated from Poland to France, published previously classified research detailing the utilization of chloropicrin as a precursor in phosgene oxime synthesis[62].

Cl3CNO2 + 2 Sn + 5 HCl + H2O → Cl2C=N-OH + 2 H2O[SnCl3]

In 1949, H. Brintzinger published a methodology for the electrolytic reduction of chloropicrin to phosgene oxime. This synthetic approach was subsequently refined in the United States[2,3].

Cl3CNO2 + 2H2 → Cl2C=N-OH + H2O + HCl

A notable synthetic route to phosgene oxime from chloronitroacetyl chloride was developed under the direction of I.V. Martynov at the State Scientific Research Institute of Organic Chemistry and Technology (GosNIIOKhT):

O2NCHClCOCl → Cl2C=N-OH + CO2

This method achieves product yields of 93-96%[60]. An alternative synthetic pathway, developed by Soviet chemists, utilizes readily available nitromethane as the starting material[64].

Additionally, dibromo- and dichloroformoxime can be synthesized via the reaction of glyoxylic acid and hydroxylamine with the corresponding halogen[33].

O=CH-COOH → HON=CH-COOH → Cl2C=N-OH

This one-pot synthesis methodology, requiring no intermediate product isolation, yields phosgene oxime in essentially pure solution form[63].

An additional synthetic approach involves the chlorination of formoxime in the presence of zinc oxide[36]:

H2C=N-OH + Cl2 + ZnO2 → Cl2C=N-OH

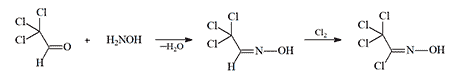

Trichloromethylchloroformoxime is synthesized via chlorination of chloral oxime (H. Brintzinger, 1952), which is itself derived from chloral hydrate and hydroxylamine:

This synthetic methodology for trichloromethylchloroformoxime was subsequently documented by chemists at the Kazan Institute of Chemical Technology in 1973[86].

Interest in phosgene oxime as a potential chemical warfare agent is due to three main reasons: first, phosgene oxime significantly facilitates the penetration of other, much more toxic agents through the skin; second, the immediate burning sensation on the face prevents the victim from putting on a gas mask in the affected area; and third, it was anticipated that phosgene oxime vapor would surpass mustard gas in its ability to penetrate clothing and cause harm.

A drawback of phosgene oxime as a chemical agent is its chemical instability, solid aggregate state, and low toxicity—significant irritating effects on the skin only occur with solutions above 8% concentration. Therefore, in the United States, pure phosgene oxime was considered a low-potential chemical agent, but the possibility of its use in combination with other agents, particularly irritants, was discussed as early as the 1970s[18].

Mechanism of Action is not fully understood. It is suggested that phosgene oxime may exert both a direct corrosive effect on cells, leading to their destruction and death, and an indirect effect:

- activation of alveolar bacteriophages,

- release of hydrogen peroxide,

- delayed tissue damage (pulmonary edema),

- apoptosis,

- elevated myeloperoxidase levels due to neutrophil infiltration at the site of injury,

- mast cell degranulation,

- phosphorylation and accumulation of protein 53 due to DNA damage,

- increased levels of COX-2 and TNFα[6,53].

The effect of phosgene oxime on mouse skin

(N. Tewari-Singh et al., 2017)

Clinical Presentation of Poisoning. Skin. Within 5–20 seconds after contact with a solution containing 8–70% phosgene oxime, a sharp pain and blanching occur on the affected skin area, which then acquires a grayish tone surrounded by erythema. Over the next 5–30 minutes, edema develops around the lesion, and within another 30 minutes, white blisters appear, which disappear fairly quickly. Within 24 hours, the edema subsides, and necrosis forms where the skin had blanched. Over the course of 7 days, a dark scab forms on the burn site. The lesion may extend to adjacent muscles and fascia, accompanied by an inflammatory response in nearby tissues. Healing of the wound may be accompanied by itching, and full recovery may take 4 to 6 months[6]. Systemic intoxication symptoms such as headache and anxiety may also occur with dermal-resorptive injury[1]. Unlike other blister agents, phosgene oxime acts almost immediately, with complete absorption through the skin surface within seconds. Even immediate decontamination cannot prevent the intense pain reaction, and regional anesthesia may be required at the hospital stage[31].

Low concentrations of phosgene oxime have a much milder effect: a 1% solution caused only slight skin irritation, while a 1.5–2% solution induced intense erythema and the appearance of itchy blisters in more than half of the test subjects within several hours[69]. Additionally, hives often spread to areas of the body that had not been in direct contact with the agent. The estimated dermal LD50 is 25 mg/kg[5].

Eyes. Eye exposure to phosgene oxime causes sharp pain, tearing, and subsequent conjunctivitis and/or keratitis. In severe cases, temporary blindness may occur[5,6].

Respiratory System. In addition to causing hives, phosgene oxime severely irritates the respiratory tract, leading to coughing, throat pain, and, at high concentrations, pulmonary edema. Pulmonary edema can develop not only after inhalation exposure but also several hours following dermal absorption. According to British data, inhaling high concentrations of phosgene oxime can result in instantaneous death[71].

Circulatory System. Absorption of phosgene oxime through the skin into the bloodstream causes dilation of peripheral vessels, with a marked increase in the number of red blood cells in the liver, spleen, kidneys, lungs, and heart, which subsequently leads to a drop in blood pressure, shock, hypoxia, and death[53].

Toxicity

There are few substances in organic chemistry that have such a powerful effect on the human body as this compound.

J.T. Hackman (1934)[87]

Phosgene oxime affects the respiratory organs, mucous membranes, and eyes and can be used in liquid, aerosol, or vapor forms.

Respiratory System. The minimum estimated effective concentration for respiratory tract damage is 300 mg/m3. The estimated median lethal dose for inhalation exposure (LC50) varies between 1 500–2 000 and 3 200 mg·min/m3[35,73].

Eyes. The first signs of eye irritation appear within 12 seconds at a concentration of 0.2 mg·min/m3. The estimated median incapacitating concentration (EC50) is 3 mg·min/m3[35].

Skin. The initial signs of skin irritation, such as burning, occur at 255 mg·min/m3, while a concentration of 365 mg·min/m3 causes intense pain. The minimum dose causing skin damage is 0.2 mg/cm2[54]. According to toxicologists from the East Germany, skin blistering occurs at concentrations ranging from 1,000 to 35,000 mg/m3[74].

Animal Species |

Route of Exposure |

Dose |

Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mouse | Inhalation | 7,000 mg·min/m3 | Observed over 10 days |

| Rat | Inhalation | 11,900 mg·min/m3 | Observed over 10 days |

| Guinea pig | Inhalation | 9,200–11,900 mg·min/m3 | Observed over 10 days |

| Rabbit | Inhalation | 11,900 mg·min/m3 | Observed over 10 days |

| Cat | Inhalation | 6,800–11,900 mg·min/m3 | Observed over 10 days |

| Guinea pig | Dermal | 25 mg/kg | In 70% aqueous solution |

| Rabbit | Dermal | 14.1 mg/kg | In 75% propylene glycol |

| Rabbit | Dermal | 26.9 mg/kg | In 75% aqueous solution |

| Rabbit | Intravenous | 2.82 mg/kg | Aqueous solution |

| Rat | Oral | 40–70 mg/kg | Approximate |

| Guinea pig | Subcutaneous | 15 mg/kg | Approximate |

Based on data from the Department of the US Army (1974)[54].

Treatment of Poisoning has not been developed, and no antidote is available. Treatment is symptomatic, focusing on preventing wound infections and managing pulmonary edema. German chemists recommended using an ammonia solution to reduce burn pain[92]. Eyes should be rinsed thoroughly with water, and no dressing should be applied. Based on recent findings regarding the pathogenesis of phosgene oxime poisoning, the use of antihistamines and anti-inflammatory drugs is considered advisable[53].

Protection. Regular clothing and even military chemical protective capes do not protect against phosgene oxime exposure. The vapors, penetrating beneath clothing and mixing with sweat, flow down the skin, causing irritation on the most sensitive areas, such as the armpits, the flexor surfaces of the elbows and knees, the buttocks, and the perineum[31]. Only a fully sealed chemical protective suit and a gas mask can provide complete protection against phosgene oxime vapors.

Decontamination. Since phosgene oxime is absorbed through the skin almost instantly, decontamination must be carried out as soon as possible after exposure. In the US Army, the standard M291 SDK is recommended for deactivation. Decontamination is not difficult since halogen oximes are easily decomposed by solutions of acids, alkalis, and oxidizing agents. For these purposes can be used, for example, an ammonia solution or 0.5% sodium hypochlorite solution. For decontamination of large surfaces and areas, solutions of strong alkalis (sodium hydroxide) in vapor form can be used[31].

Detection. The American chemical agent detection kit M18A2 can identify phosgene oxime at concentrations as low as 0.5 mg/m3, while the M90 detector can detect it at 0.15 mg/m3[73]. In Kuwait, the M18A2 detection kit and field mass spectrometers were used for sample analysis[31].

Origin and Application of Phosgene Oxime: A Historical Overview

Its combination of highly painful skin attack with the possibility of a lingering death by asphyxiation undoubtedly makes it one of the nastiest agents available.

J. P. Robinson (1968)[93]

Germany. Virtually all halogen oximes discussed previously were first synthesized in Germany. Since 1938, German chemists had been closely monitoring Soviet research on "Nettle Gases," as they believed these substances possessed significant military importance, provided their stability and shelf life could be improved by adding certain admixtures The largest part of these experiments took place in 1942/43.[94]

Since phosgene oxime/mustard gas mixtures were reported to have been found in Russia, and the Germans believed the Russians might use this agent, it was decided to conduct their own research in the military chemical laboratory in Spandau. However, it was discovered that the phosgene oxime/mustard gas mixtures were ineffective from a military standpoint, as the irritating effects of phosgene oxime and the vesicant properties of mustard gas were diminished when combined[92].

German chemists considered phosgene oxime unsuitable for military applications. However, prior to World War II, bromoacetone oxime and several of its homologues were evaluated as potential combat chemical agents[21]. The development of the "second generation of chloroformoximes" was conducted with the participation of one of the leading Nazi military chemists — Sturmführer Herbert Brintzinger[85].

Poland. Research on phosgene oxime synthesis in Poland was conducted by Professor E.V. Gryszkiewicz-Trochimowski from the Gas Mask Institute. In 1933, he developed an innovative method enabling industrial-scale production of this novel chemical warfare agent[62]. In Poland, phosgene oxime was designated under the code TSD[61].

Japan. German-Japanese collaboration in chemical warfare agent development and production intensified beginning in 1923. Along with technological transfers, the Japanese gained access to recent German innovations, including phosgene oxime. Following initial evaluations, they deemed it unsuitable as a chemical warfare agent due to its poor hydrolytic stability[32], yet continued experimental investigations. The infamous Unit 731, notorious for conducting human experimentation with toxic gases, also experimented with phosgene oxime (code name "Blue"). Following Japan's defeat, the most valuable "scientists" and all documentation related to chemical warfare agent development were transferred to the United States.

Italy. Italian chemists and toxicologists made significant contributions to the study of "urticant gases". In 1930, Italian chemist de Paolini synthesized dibromformoxime, and in the late 1930s, M. Milone synthesized and characterized the urticant and irritant properties of oximes and isonitro derivatives of chloroacetone and chloroacetophenone[68]. In 1983, P. Malatesta et al. published the first publicly accessible results of human toxicological trials involving phosgene oxime[69].

United States. Before World War II, the U.S. Army Chemical Warfare Service conducted tests of phosgene oxime not only on laboratory animals but also on volunteers[47]. During the war, the physiological effects of phosgene oxime continued to be studied in the toxicology laboratory at the University of Chicago. In the mid-1950s, tests were conducted in the U.S. on a combination of phosgene oxime and nerve agents — tabun, sarin[45], and soman, and later, phosgene oxime and V-agents[22]. There are mentions that a 50/50 mixture of sarin with phosgene oxime was "significantly more toxic than 'pure' sarin."[72]

In 1984, a complete study of the inhalation toxicity and eye irritation of the blistering agent phosgene oxime (CX) was conducted [98].

In 2014, the U.S. Army Edgewood Chemical Biological Center (ECBC) conducted animal studies on the "Toxicological Evaluation of EA 5680, EA 5761 (Bare Skin and Dry vs Wet Clothing), and GD (Dry vs Wet Clothing) in the Rabbit."[77]. The substance EA 5761 is a mixture of 56% soman and 44% phosgene oxime[78].

United Kingdom. During the Second World War, renowned military chemists such as H. McCombie and B. C. Saunders investigated the physiological effects of dichlor- and dibromoximes[70]. Concurrently, a structurally similar compound, Trichloracetaldoxim, underwent evaluation as a potential vesicant chemical warfare agent in the United States and the United Kingdom.[79]

Afghan mujahideen posing in gas masks captured from the Soviet Army

Soviet-Afghan War (1979–1989). According to American official sources, the Soviet Army employed at least three types of chemical agents during the Afghanistan conflict: mycotoxins, an unidentified narcotic gas, and phosgene oxime[30].

Iran-Iraq War (1980-1988). Throughout the conflict, U.S. intelligence repeatedly received reports of Iraqi forces deploying an unidentified chemical agent that induced immediate painful irritation of eyes and cutaneous tissues, followed by the development of pale lesions that progressed to open wounds within a week. Iranian forces also reported that their chemical detection systems had registered instances of phosgene oxime deployment. However, to date, the alleged use of phosgene oxime by Iraq remains unsubstantiated[45].

In 1991, following the conclusion of the Gulf War, a container of toxic liquid belonging to the Iraqi military was discovered in Kuwait. Dermal exposure to several droplets of this substance resulted in chemical burns to one serviceman. Initial laboratory analysis of the samples indicated traces of sulfur mustard and phosgene oxime[31]. However, subsequent verification analyses revealed only the presence of concentrated nitric acid[44].

Bulgaria. Beyond the Soviet Union, research on phosgene oxime was conducted within the former socialist bloc at the Sofia Medical Institute. In 1957, institute researchers published several studies detailing the pathological manifestations of this chemical agent's toxicity in canine subjects[4].

The German "Red Cross" for the Red Army

To sesure a great tactical superiority by causing immediate and severe skin blisters by the use of a gas was the goal of extensive and comprehensive Russian investigations. The choice has apparently fallen on Phosgene oxime.

W. Hirsch, former Chief of the Gas Protection Unit (Wa Prüf 9)

In Germany, chemical agents of this group were assigned the code designations "Red Cross" (Rotkreuz) or "Yellow Cross 3" (Gelbkreuz 3).

German intelligence reports indicated that by 1939, the Russians had not yet succeeded in stabilizing phosgene oxime. However, in 1940, there were suggestions that the Russians had discovered stabilizers and that the compound would soon be ready for military use. It was claimed that the stability of phosgene oxime did not exceed three months[94].

Information obtained from captured Soviet soldiers and deserters suggested that Nitrogen Mustard and Phosgene Oxime, described as new and highly secret war gases, were allegedly being produced in large quantities. For better preservation, the gases were reportedly stored in glass ampules measuring 50 cm in length and 15 mm in diameter. These gases were said to remain stable for six months to one year[94].

In 1942, German intelligence received information from a reliable source about a novel Soviet chemical warfare agent designated as Lebeda (or Lebedan). The nomenclature is hypothesized to be associated with Academician S.V. Lebedev, who served as the head of the Chemistry Department at the Military Medical Academy from 1917 to 1933 and was potentially involved in the agent's development. The intelligence report described Lebeda as a "reddish-brown liquid smelling like rotten pears, and having on the skin an effect similar to that of the mustard gas or lewisite, but considerably quicker in action. The skin lesions caused by this new gas had a great similarity to those produced by strong acids. It was dispersed preferably by aircraft. This information is suggestive of phosgene oxime. ...no known protective measures were deemed effective at the time"[17].

German and subsequently American intelligence postulated that the designation might conceal various chemical compounds, including ethyl- or methyldichloroarsines, chlorine trifluoride, and even tabun, which was known for its pleasant fruity odor[17]. However, the description most closely aligned with phosgeneoxime dissolved in ethyl acetate, a solution with a distinctly pear-like aroma, albeit more acrid[75]. Notably, ethyl acetate was utilized in the Soviet Union as a solvent and stabilizer for phosgene oxime[52].

In fact, the possibility of phosgene oxime industrial production in the USSR during that period is contested by Lev Fedorov, a recognized authority in Soviet chemical program research. After dedicating years to examining archives of the Soviet military-chemical complex, he failed to discover evidence of even experimental production of this chemical warfare agent during World War II. However, in documentation from the early 1950s, he did locate references to "significant research involving phosgene oxime as a chemical warfare agent"[42].

Other documents also confirm the strong interest of the Soviet leadership in further development of this direction. For instance, in a report by the USSR General Prosecutor's Office regarding deficiencies in the work of the People's Commissariat of Chemical Industry, it states that "since 1936, the question of using phosgene oxime, a semi-persistent toxic agent with rapid cutaneous action, has not been resolved. Despite knowing about the valuable combat properties of this substance and having a method for its industrial production, developed at NII-42, the People's Commissariat of Chemical Industry did not raise the question of adopting this toxic agent into service and stopped all work on improving its technology. As a result, in 1941, when the question about this toxic agent was positively resolved, several technological aspects remained underdeveloped"[43].

After the end of the war, Soviet intelligence agencies unsuccessfully tried to find applications for phosgene oxime. G. M. Mairanovsky — the head of the toxicology laboratory of the Soviet secret police (NKVD-MGB), known for their intelligence and political repression efforts, which dealt with eliminating political opponents of Soviet power using poisons, wrote: «During the research we introduced poisons through food, various drinks and used hypodermic needles, a cane, a fountain pen and other sharp objects especially outfitted for the job.We also administered poisons through the skin by spraying or pouring oxime (fatal for animals in minimal doses). But this substance proved not to be lethal for people, causing only severe burns and great pain.»[51].

Not only German intelligence suspected the USSR possessed phosgene oxime. According to data obtained by the CIA, in late 1948, "phosgene oxime, has been field-tested and accepted for use in a stabilized form, probably by special units of the Red Army"[48]. If phosgene oxime for special operations was produced not on an industrial scale, but on a small-tonnage experimental production, then only a very limited number of people might have known about its existence. It suffices to recall that at the State Research Institute of Organic Chemistry and Technology (GosNIIOKhT), no more than 20 people had complete information about the development of third-generation toxic agents under the "Foliant" program[59].

Beginning in 1979, multiple independent sources including mujahideen fighters, refugees, journalists, and Soviet defectors reported the deployment no recognized class of chemical agents by Soviet forces in Afghanistan. One of these chemical agents was characterized by its extraordinarily severe effects on human tissue. Journalists and victims of the attacks consistently documented the distinctive blue-black discoloration and rapid decomposition of skin occurring within 1-3 hours post-exposure. The tissue deterioration was so severe that attempts to transport deceased victims resulted in extreme friability of the corpses, with witnesses reporting that "fingers being punched through the skin and limbs falling off". Based on analysis of these reports, U.S. experts concluded that only two known chemical warfare agents could produce such severe tissue degradation patterns: phosgene or phosgene oxime[32].

Indeed, in the fulminant form of phosgene intoxication, death occurs within 2–3 seconds[58], during which the skin may acquire an ash-gray hue characteristic of central (pulmonary) cyanosis. However, in phosgene poisoning, bodily tissues remain largely intact, in contrast to phosgene oxime, which induces extensive necrosis. Experiments conducted by the Chemical Corps in 1955 demonstrated that exposure to phosgene oxime vapors caused calf skin (the most desirable test animal) to transform to a purplish-black coloration, subsequently transitioning to a deep broown shade[57].

Sovien Helicops just dropped canisters that are exploding into yellowish cloud (Faizabad in Afghanistan)[56]

The body of an Afghan, photographed shortly after the attacks, shows blackened skin caused by internal bleeding rather than burns, as the hair remains intact. Experts speculate that the individual may have been killed by a chemical agent, possibly phosgene oxime[56].

In June 1981, Dutch journalist Bernd de Bruin documented a chemical weapons deployment by Soviet forces on a village near Jalalabad. He captured footage of a military helicopter releasing several chemical agent containers, which upon detonation generated a yellowish vapor cloud. Five hours post-incident, he photographed the remains of one of the Afghan casualties, whose skin had blackened, which the journalist attributed to internal hemorrhaging. Several subject matter experts suggested the victim's pathology was consistent with phosgene oxime exposure[56]. The Soviet authorities categorically denied these allegations and demanded empirical evidence, which U.S. intelligence services were unable to provide.